Woodchucks: Garden Raiders or Good Neighbors

By Margaret Klein Wilson, Fairfax Master Gardener Intern

Woodchucks Marmota monax, aka groundhogs or whistle pigs, are a fixture in the woodlands and meadows of the northern and eastern United States and across southern Canada. These characterful rodents are also common to suburban yards and grassy highway corridors, and easy to spot. Active and feeding in the early morning and late afternoons, a woodchuck cuts a confident profile: upright and balancing their brownish-gray, coarsely haired body on the tripod of their stubby tail and sturdy hind feet. Whether surveying for danger or “pouring it on” in a dead run back to their burrow, woodchucks exude energy and a sense of mission.

At this time of year, woodchucks are on a mission — packing in as much food and putting on a layer of fat to last them through five or six months of deep sleep. True hibernators, woodchucks go to ground and seal up their burrows behind them by the end of October. Their body temperature drops from 99 degrees to 40 degrees (37 to 4 degrees C), and their heartbeat plummets from 100 beats per minute to a nearly imperceptible 4 beats per minute.

At this time of year, woodchucks are on a mission — packing in as much food and putting on a layer of fat to last them through five or six months of deep sleep. True hibernators, woodchucks go to ground and seal up their burrows behind them by the end of October. Their body temperature drops from 99 degrees to 40 degrees (37 to 4 degrees C), and their heartbeat plummets from 100 beats per minute to a nearly imperceptible 4 beats per minute.

When woodchucks emerge gaunt and lean from their dens in February or March, and expected to see their shadow, they are barely a shadow themselves. Finding food, seeking out a mate, re-opening or digging a fresh burrow and commencing a new generation of woodchucks are urgent matters. Their diet is mainly vegetarian, including grasses, clover, berries and fruits in season, flowers, plantains and your fresh garden produce. Grasshoppers, June bugs, beetles and other large insects add some variety. Gnawing on the bark of hickory and maple trees is part hunger and part dental necessity to whittle the length of their front incisors. Teeth, speed, raking front and hind claws and a thick skin are an adult woodchuck’s main defense against its few predators and best hope for living five or six years.

So is a good burrow.

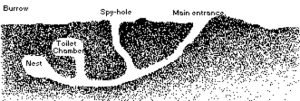

Weighing in at 8 to 12 pounds (3.5 to 5.5 kg) and about 20 inches long (50 cm), woodchucks are superb, compact excavators, capable of digging a complex burrow system or two in a season. Woodchucks like to burrow in open areas, preferably on a slope with a good view, but may choose digging in between tree roots, close to building foundations or along stone walls. Burrows have several entrances, but the front door is the only one characterized with a patch of fresh dirt to mark the 10 to 12 inch opening (25-30 cm). Other entry points are smaller and harder to locate. The main channel drops immediately from the front entry to a depth of 2 to 6 feet (0.6 to 1.5 m) and then rises again, extending more than 40 feet (12 m) and with multiple rooms along the way designated as nesting or “bio” areas. This keeps the nesting chamber clean and more disease free.

Woodchucks begin to mate in early spring of their second year, producing a litter of four to six “chucklings” in April to May. The females are the lone parents and complete raising their offspring to independence within 10 to 12 weeks. Then the maternal cord is cut clean. Evicted or abandoned by early August, the young are on their own and vulnerable to predators such as raccoons, hawks and foxes. As a result, they may seek easier shelter, under buildings or in a stone wall.

The good news is that burrows are dynamic. Renovations and revolving tenants are the norm. Abandoned burrows are one of the chief contributions woodchucks make to their environment, providing shelter to other mammals and reptiles. The opening scene of the children’s book, The Adventures of Johnny Chuck, by Thornton W. Burgess, centers on young Johnny, fresh out of hibernation, gifting his home burrow to a skunk. Then Johnny ventures to a neighboring meadow where he usurps an older chuck’s burrow after a lively tussle.

The good news is that burrows are dynamic. Renovations and revolving tenants are the norm. Abandoned burrows are one of the chief contributions woodchucks make to their environment, providing shelter to other mammals and reptiles. The opening scene of the children’s book, The Adventures of Johnny Chuck, by Thornton W. Burgess, centers on young Johnny, fresh out of hibernation, gifting his home burrow to a skunk. Then Johnny ventures to a neighboring meadow where he usurps an older chuck’s burrow after a lively tussle.

The bad news is that active burrows may become a target when humans want to discourage or eradicate neighborhood woodchucks.

Voracious foraging in more populated areas sets the stage for human and woodchuck conflict. When gardens are raided, and friendlier methods of discouraging woodchucks don’t keep them out of the garden, the next step some gardeners take is to harass the woodchucks away from their burrows.

Late summer triggers unfettered feeding for woodchucks and other animals. The countdown to hibernation is a motivator, but there is also an abundance and variety of food to eat. When the foraging veers from wild offerings to cultivated gardens, the result is a gardener focusing their unfettered frustration on the known garden raider. If the first line of defense — pinwheels, garden hoses and fluttering shiny objects — doesn’t deter the invader, the next step is a good fence.

Standard chicken wire or welded wire, 3 to 4 feet tall (1 to 1.5 m), with an L-footer base buried and secured to the ground is effective, especially if the top 18 inches of the fence is loosely attached and bends out. Woodchucks will climb sturdy walls and trees, but wobbly wire may defeat them.

The worst news for the woodchucks is when those efforts to control, expel or eradicate them escalate to fouling or blocking off burrows entirely. For gardeners and farmers whose crops are suffering significant damage, this is the last and understandable resort. Care must be taken with how this is achieved.

Stripping vegetation well away from burrow doors will spook a chuck. Fouling the tunnel with decaying grass clippings, clumps of urine soaked cat litter or stuffing rags or newspaper covered in olive oil (that will turn rancid) make the burrow less desirable. Flooding will not work as burrow tunnels are engineered not to take on water. Observe the entry points for activity for several days to monitor before closing.

Closing a burrow is humanely done in mid-summer to late September after it is determined that the space is vacant. The goal is not to trap young or hibernating animals inside but to close down the burrow for further habitation so the animal can relocate. Place 3-foot squares (1 m) of heavy-gauge welded fence wire over the holes and bury them at least 1 foot deep (30 cm), securing them with rocks or landscape staples.

Woodchucks do hold their place in the firmament of nature, as a step in the food chain, a source of providing shelter for other creatures and being charming homebodies who love to graze morning and night and nap in the sun. May gardeners build good fences as needed, so all can be good neighbors.

Resources

Woodchucks, Mass Audubon

Woodchucks (Groundhogs) as Neighbors, The Wildlife Center of Virginia

A Naturalist’s Guide to the Year, by Howard Smith

Handbook of Nature Study, by Anna Botsford Comstock

The Adventures of Johnny Chuck, by Thornton W. Burgess