What We Need to Know About Soil Remineralization

By Janet Scheren, Fairfax Master Gardener

Most gardeners are already aware of the vital need for sufficient organic matter in the soil. It feeds the microbes that feed the plants in exchange for their carbohydrate-rich exudates. But that’s not all these microbes do. They build the soil structure by excreting a mineral rich cement like substance. They also digest and feed these minerals to the plants themselves. Without sufficient mineral stores in the soil, our busy soil microbes don’t have the raw materials needed to do their critical work, and the plants they feed won’t have access to the minerals necessary to build healthy tissue to fend off pests and diseases.

Why Soil Mineralization Matters

Why Soil Mineralization Matters

When you’re planting crops — even in your home garden — you are extracting more nutrients from the soil than you would with typical landscape plants. This occurs in part because many crops are heavy feeders. While crop rotation strategies and cover crops can help minimize the drain on the soil, it’s important to replenish depleted nutrients. In addition to compost, many agricultural scientists and permaculture experts are now looking to soil remineralization to ensure a thriving garden. They suggest that pests or diseases in your garden point to an underlying problem that needs to be resolved. Put another way, pests and diseases are the symptoms, not the underlying problem.

A second reason to care about the minerals in your soil is that when we make the effort to raise fruits and vegetables, we want these crops to provide us with dense nutrition. If our crops don’t have the nutrients they need to defend against pests and diseases, they won’t be able to provide optimal nutrition for us.

In nature, there are three ways that soils are regenerated. Pulitzer Prize-winning author and professor from the University of California, Los Angeles, Jared Diamond, details in his book, Collapse, that soils that have been leached of nutrients can be renewed by three major processes: volcanic eruptions spewing fresh materials from within the earth; the advances and retreats of glaciers, which strip, dig up, grind up and redeposit the Earth’s crust; and the slow uplift of crust, which has contributed to the fertility of large parts of North America, India and Europe. Collapse details these as critical factors that caused ancient civilizations to fall. Key among these were environmental degradation and inability to replenish soil and other natural resources.

Historically, agricultural societies started in river valleys where annual floods or mineral-rich rain flowing down the mountains replenished and remineralized the soil on a regular basis. Each crop harvest takes with it the minerals that are most biologically valuable and available. Over time, if this essential mining is not addressed, farmers find that their soils have worn out.

Awareness of soil remineralization has now moved beyond cutting-edge permaculture and regenerative agriculture practitioners to several universities in the United States, the UK, Australia and Japan, which are conducting studies on it. In addition, several non-profit, research-oriented organizations have been founded to study permaculture, soil mineral content and nutrient density in human food.

These researchers are looking at several types of minerals and rock powders to add minerals back to the soil. These roughly correspond with the remineralization processes in nature.

Glacial rock dust is mined from glacial moraine that is left behind as a glacier recedes. While it doesn’t have as many rare elements as some of the other rock dust products, it can provide a balanced supply of magnesium

Basalt rock dust is made from volcanic dust and has a large host of the rare elements. In addition, it is rich in silica. It also weathers quickly, which enhances bioavailability. It’s a good source of phosphorus and potassium. Because there is ample supply of basalt, it is one of the cheaper rock dusts to buy.

Azomite was formed from volcanic dust that settled in an ancient seabed in Utah. This product is hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate along with a multitude of trace minerals. Its main drawback is that it contains high amounts of metal ions, including aluminum, lead and arsenic.

Gypsum is calcium sulfate. While it is not a composite material, it’s a valuable rock dust that helps to aerate compacted soil, removes salts from the soil, and provides an excellent source of calcium and sulphur, which helps balance soil ph.

Fish Emulsion and Liquid Seaweed are products high in trace elements, are bioavailable and provide a good source of organic matter as well.

How Healthy is Your Soil?

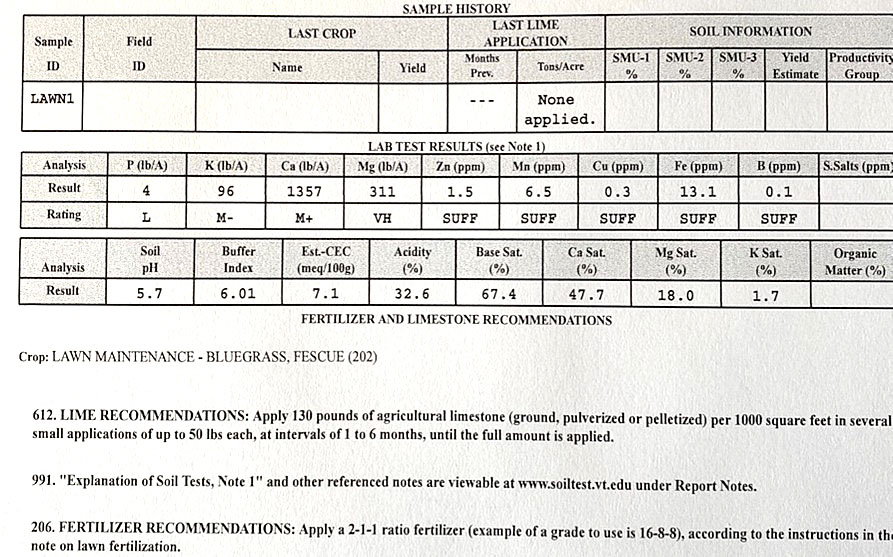

You can get a handle on the fertility and mineral content of your soil by having it tested by a reputable lab. The Virginia Tech Soil Testing Laboratory, in affiliation with Virginia Cooperative Extension, offers an excellent soil test service at a reasonable price. The test checks your levels of key macro and micronutrients: phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, zinc, copper, iron, manganese and boron. These are nine of the 16 macro and micronutrients considered essential for plant health. It also reports out soil pH, a measure of the acidity or alkalinity of your soil and its Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC), a measure of how well the soil retains nutrients against the leaching effects of rain.

If your soil test comes back with suboptimal levels of one or more key elements, you will want to amend your soil. The synergy of all of these minerals working together with organic matter and essential microbial life in your soil forms the foundation for healthy plants.

If your soil test comes back with suboptimal levels of one or more key elements, you will want to amend your soil. The synergy of all of these minerals working together with organic matter and essential microbial life in your soil forms the foundation for healthy plants.

Leibig’s Law of the Minimum

While this law may sound obscure, it’s the reason we pay attention to all of the nutrient levels in our soils. Fairfax County soil, which is composed of weathered clay from the gradual erosion of the Piedmont, usually contains all the elements needed to support plant growth, but not always. Leibig’s law states that growth is dictated not by total resources available, but by the scarcest resource. So, regardless of how abundantly rich you soil is in all the other trace minerals, if one is missing or in low amounts in the soil, it will inhibit optimal growth of your crops.

Taking a parallel from human health, we know that while it’s a good idea to take a multi-vitamin, we should focus on getting most of our nutrients from a variety of healthy fruits and vegetables. We’ve learned that there are nutrients in foods that we may still have not discovered or fully understand. Additionally, we know that combinations of nutrients in our foods are synergistic. Think of your soil in the same way. That’s why there is so much interest today in ways to remineralize our soils.

Other Considerations

In addition to having sufficient minerals in the soil, we need to get the minerals out of the soil and into the plants. Several factors can limit a plant’s ability to access the minerals in the soil.

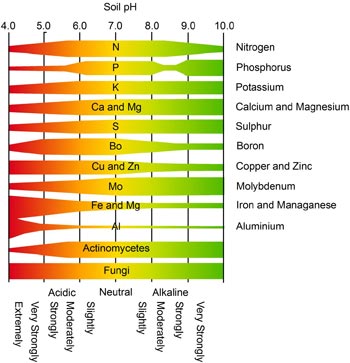

Key among these is soil pH. The pH of a soil influences the entire soil chemical environment and fundamentally determines nutrient availability as shown in the chart. An essentially neutral pH provides maximum access to most of these key minerals. A soil pH of 6.5 to 7.0 is often considered ideal for most plants; however, you’ll want to check the pH of individual crops you intend to grow.

Availability of nutrients at various pH levels

A third factor is the biological health of your soil. Microbial activity and the full range of worms is critical to the food web. Lack of organic matter, use of pesticides or herbicides or inadequate soil moisture all limit microbial activity and life in your soil, and as a result the ability of your crops to get the nutrients they need from the soil.

There is still much to learn in this field. The University of Massachusetts, Pennsylvania State University, The University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, The University of Wisconsin and the University of Hawaii are among those universities conducting research in this field. Also included are the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom, and the University of Kagawa in Japan. It will be interesting to follow the evolution of the science as they learn more about nature and the health of plants.

Resources

• Collapse: How Societies Choose To Fail or Succeed, by Jared Diamond, 2004

• Understanding Your Virginia Soil Test Report, Gil Medeiros, Former Fairfax Master Gardener

• Understanding Soil Fertility, Mary Jo R. Gibson, Master Gardener, Columbia County, Pennsylvania State

University Extension

• Using Brix as an Indicator of Vegetable Quality: Linking Measured Values to Crop Management,

Matthew D. Kleinhenz and Natalie R. Bumgarner, Department of Horticulture and Crop Science, Ohio

State University

• Changing the pH of Your Soil, Marjan Kluepfel, Bob Lippert and Joey Williamson, Clemson Cooperative

Extension

• Role of Silicon in Enhancing the Resistance of Plants to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses, Jian Feng Ma, Soil

Science and Plant Nutrition, 50:1, 2004

• Soils and Plant Nutrients, David Crouse, North Carolina State Extension